The Maverick Philosopher links to a global warming article by a Harvard Physics professor. The gist of it is that the current “climate crusade” against global warming is a moral epidemic. The notion that increasing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, notably carbon dioxide, will have disastrous consequences for mankind and for the planet, is based on contested science and dubious claims, he says.

The Maverick Philosopher links to a global warming article by a Harvard Physics professor. The gist of it is that the current “climate crusade” against global warming is a moral epidemic. The notion that increasing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, notably carbon dioxide, will have disastrous consequences for mankind and for the planet, is based on contested science and dubious claims, he says.This is a blog which is concerned with ‘sceptical’ issues, so it ought to be concerned with global warming scepticism. But that means scepticism in the strict and proper sense: not holding any positive opinions about p (or not-p), but rather holding that the evidence for p (or not-p) is not sufficient, or reasonable, or conclusive. Humanity is divided into fundamentally two types: those who sit at the front of the class and listen with rapt attention to everything Teacher said (as well as sucking up and toadying to Teacher and all other forms of authority with unquestioning acceptance); and those who sit and the back and talk and throw objects at those in the front, and generally disrepect all forms of authority. True believers at the front, sceptics and disbelievers and mockers and scorners, at the back. The world would be a disastrous place if either type predominated. A world of believers would be dreary and authoritarian if their beliefs were consistent. If not consistent, in would be full of more bloodshed and warfare. In a world of mockers and sneerers, nothing would ever get done, and it would also be boring with no true believers and boy scouts to sneer at and mock.

I am a global warming sceptic in the sense that I remain unconvinced that it exists. Equally I remain unconvinced that it doesn’t exist - being a cautious fellow and mindful of the possibility that it does, I very rarely use a car (the one I bought three years ago has done little more than 5,000 miles), and my heating bills are lower than anyone I know. I am both a global-warming and and anti-global warming sceptic.

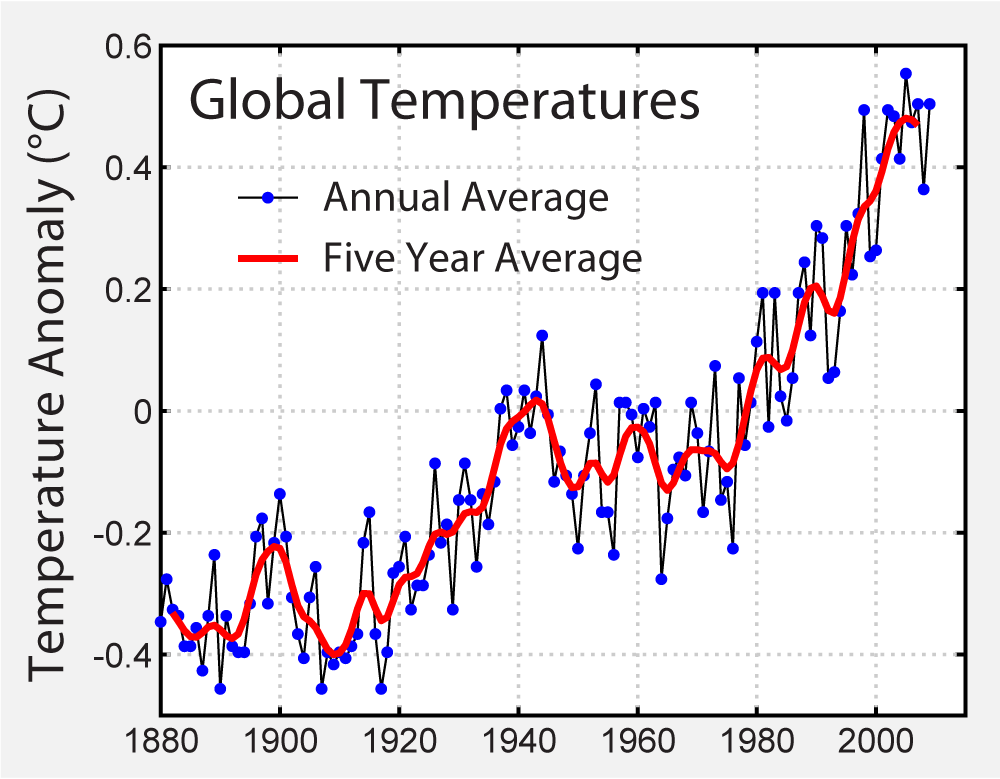

Why am I sceptical that it exists? I see a scientific model, and empirical evidence adduced in support of the model. Taking the empirical evidence first, it is primarily statistical, given that the actual temperature data is noisy and subject to error. All kinds of extrapolation and curve-fitting is required to produce the neat ‘hockey stick’ graph that appears to show a constant temperature from the year 1000 until about 1850, when the temperature began to rise like the blade of a hockey stick. Since I don’t accept probabilities between 0 and 1, I don’t accept statistics. The temptation to select data to fit the theory is simply too strong. On the side of the model, there is a robust physical model which predicts rises in temperature for increasing amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The problem is that water vapour is also a powerful greenhouse gas, and the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere is difficult to model. Add to that the fact that the effect of carbon dioxide obeys a logarithmic law – to get the same effect as doubling the amount, you have to double it again, and again) – a fact which I have never seen mentioned in any of the global warming propaganda in schools and the mainstream media. Nor is it mentioned in the truly horrible Wikipedia article on the Global Warming controversy. The article simply repeats over and over that there is a scientific consensus on GW (the word ‘consensus’ is repeated 26 times). It gives no substantial arguments or reasoning or basis facts on either side of the debate.

This will probably provoke all sorts of rude emails, to which I say, don’t be rude, just give me a neat Fermi argument to prove to me beyond reasonable doubt that a serious global warming problem exists. I am not interested in what any scientists conclude. I am interested in the basic evidence they have used, and the reasoning process which leads them to their conclusion. Possibility of another £5 Waitrose voucher for any decent answers (I am the final judge however).

I just spotted

I just spotted