Originally published here.

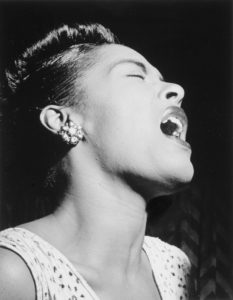

Them that's got shall get Them that's not shall lose So the Bible said and it still is newsSo Billie Holiday sang, probably alluding to Matthew 25:29 (‘For whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them’) or Luke 8:18 (‘whosoever hath, to him shall be given; and whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken even that which he seemeth to have’), but that’s irrelevant. The point is that the subject of the verb ‘said’ is ‘the Bible’, and as Joshua Harris objects, the Bible cannot ‘say’ anything. It’s ‘an inanimate object, not an intellectual agent’. Well, perhaps we can change that to ‘it says in the Bible – who then is the impersonal ‘it’? What about ‘Matthew says that whoever has will be given more. What if Matthew didn’t write that gospel? Would it then be false that Matthew says that?

It is key to the theory of reference that I shall propose that we refer by means of the signs we use. Granted, it is through our will and agency that we produce signs: words and sentences that we utter or write, nods, winks, shrugs and other forms of non-verbal signification. But once the signs are in public view, it is they which do the work, as David Cameron found to his cost. Were intentions sufficient to make our meaning clear, there would be none of the confusion, ambiguity and lack of clarity that fill every waking moment.

Indeed, why should intentions or thoughts or stuff inside have anything to do with how we express what some text means or says? Suppose that the thought which Bob expresses by the words 'Sinners will be punished' is the thought that we would express by 'hamburgers with relish are delicious'. So when Bob says 'Matthew 25:46 says that sinners will be punished', he thinks that Matthew is saying something about hamburgers. Now what he thinks is false, but what he says is perfectly true. Matthew 25:46 indeed says that sinners will be punished, or something like that. The stuff inside our heads is just not important at all, indeed, it is questionable whether the Bob example is even coherent. Are we supposing that he has a kind of private language which, if there were a dictionary for it, would translate the spoken word 'sinners' into the mental word 'hamburgers'?

This is fundamentally connected with what I will have to say later about reference. Dale Tuggy asks here about some person who has ‘a goofy and anachronistic interpretation of the Bible, on which both God and Moses are avatars of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. Then what the Bible actually asserts may hardly enter his mind, as he's indirectly quoting it. But I think he [would] still be referring to what it actually asserts, by using the phrase that you've said.’ I agree. In the indirect quotation that he utters, the word ‘God’ refers to God, and ‘Moses’, to Moses. No avoiding that. Perhaps he means to refer so something else, but that does not matter. It is words that refer, not people. But more later.

Bill Vallicella, the famous

Bill Vallicella, the famous  Last month my publisher gave the green light to start work on The Same God? Reference and Identity in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Scriptures. Yes, that old question of whether Muslims worship the same God as Christians, which surfaced again last year when Larycia Hawkins, an associate professor at Wheaton College, was

Last month my publisher gave the green light to start work on The Same God? Reference and Identity in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Scriptures. Yes, that old question of whether Muslims worship the same God as Christians, which surfaced again last year when Larycia Hawkins, an associate professor at Wheaton College, was