Summa 1-6 Summa 7-10 Summa 14-18

Summa 19-21 Summa 22-24 Summa 25-26 Summa 36-38 Summa 39-43 Summa 44-49

[The object of conception] is not the image of an animal—it is an animal. I knowPerhaps this is what is driving Bill's argument from the premiss ‘Tom is thinking of something’ to the conclusion ‘Tom’s thinking has an intentional object’? Tom is thinking of unicorn, Tom is thinking of something other than the thought of a unicorn, ergo Tom stands in some 'intentional relation' to some quasi-unicorn, an 'intentional object'.

what it is to conceive an image of an animal, and what it is to conceive an

animal… The thing I conceive is a body of a certain figure and colour, having

life and spontaneous motion. The philosopher says, that the idea is an image of

the animal; but that it has neither body, nor colour, nor life, nor spontaneous

motion. This I am not able to comprehend. (Essays on the Intellectual powers

of man, 4.2, 321-2)

There is a clear sense in which every intentional mental state 'takes anIn other words, he clearly regards as valid the inference from (A) to (B) below:

accusative,' 'is of or about an object.' That object could be called the

intentional object. Accordingly, whether I want a three-headed dog or a

one-headed dog, my wanting has an intentional object.

A further characteristic is necessary to distinguish queer terms from other non-referring terms like ‘dragon’, ‘goblin’, ‘ghost’ and so on. The reason that some people believe these terms refer is unconnected with the reason that metaphysicians believe that there exist such things as intentional objects, or universals, or haecceities. People believe that ghosts exist because they believe that certain objectively verifiable phenomena are evidence for the existence of ghosts. For example, the photograph on the left undoubtedly exists. It is a real photograph that anyone reading this blog can see. And some people may believe it is evidence for ghosts.

A further characteristic is necessary to distinguish queer terms from other non-referring terms like ‘dragon’, ‘goblin’, ‘ghost’ and so on. The reason that some people believe these terms refer is unconnected with the reason that metaphysicians believe that there exist such things as intentional objects, or universals, or haecceities. People believe that ghosts exist because they believe that certain objectively verifiable phenomena are evidence for the existence of ghosts. For example, the photograph on the left undoubtedly exists. It is a real photograph that anyone reading this blog can see. And some people may believe it is evidence for ghosts.As discussed yesterday, a 'Brentano equivalence' holds when we can convert existential sentences of the form 'an A-B exists' and categorical sentences of the form 'Some A is B'. The Brentano thesis is that every such (genuinely) categorical sentence is convertible.

This effectively amounts to the claim that any sentence of the form 'something is such and such' is existential. If anything is such and such, then that thing is an existing thing. The range of our natural language quantifiers 'every' and 'some' covers the entire realm of existence. Every thing is an existing thing.

There are strong arguments for this thesis. But there are strong arguments against, as well, which brings us back to the problem of intentionality. Surely the following inferences are all valid.

The problem is that any of these antecedents could conceivably be true, the inference seems valid, yet the 'something' in the consequent does not appear to be any existing thing. Clearly Jake can be deludedly looking for a Surrey gold mine, and so looking for a mine, and so looking for something. Yet, as far as we know, there are no gold mines in Surrey. The simple categorical sentence 'Jake is looking for something' can be true, without requiring that the something exists, contra Brentano.

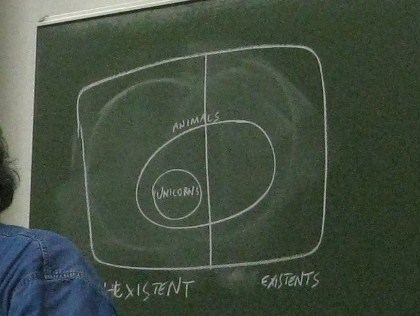

Hence my objection to Bill's claim that 'We sometimes think about the nonexistent'. 'The nonexistent' is an abstract noun phrases built out of an adjective, like 'the unemployed', 'the French', 'the damned', which appear to refer to a whole class of things (unemployed people, French people, damned souls). If the same is true of 'the nonexistent', then it refers to a whole class of things - things which do not exist - and we can divide all things in reality into those which do exist (mountains, horses, yellow buttercups) and those which do not (golden mountains, unicorns, blue buttercups, four-leaf clovers and so on). You can see the idea in the picture on the left (from the Logic Now and Then symposium in 2008 - I don't remember who the speaker was).

Hence my objection to Bill's claim that 'We sometimes think about the nonexistent'. 'The nonexistent' is an abstract noun phrases built out of an adjective, like 'the unemployed', 'the French', 'the damned', which appear to refer to a whole class of things (unemployed people, French people, damned souls). If the same is true of 'the nonexistent', then it refers to a whole class of things - things which do not exist - and we can divide all things in reality into those which do exist (mountains, horses, yellow buttercups) and those which do not (golden mountains, unicorns, blue buttercups, four-leaf clovers and so on). You can see the idea in the picture on the left (from the Logic Now and Then symposium in 2008 - I don't remember who the speaker was).